When I moved to DC in January 2016, I split a studio apartment with an artist. We were underemployed, underpaid and stressed out, so we did what any early-twenties roommates would: We got really into making Crock Pot cakes.

It’s honestly generous to call what we made “cakes.” The dessert, whatever it was, was cheap and simple, transforming boxed cake and pudding mixes into something that vaguely resembled lava cake. The best part was the smell. We always went for double chocolate everything, and our apartment retained that eau de Hershey Factory for hours.

When my roommate moved out a few months later, she took her Crock Pot with her, and that was the end of my strange cake indulgence. I didn’t think much about Crock Pots until this week, when I learned about the appliance’s roots in traditional Jewish cooking, and its precarious place in the push for gender equality.

You can trace any Crock Pot’s origin back to Lithuania. On Friday evenings, Jewish households prepared for the Sabbath by planning a meal in advance. People would fill crocks with meat, vegetables and beans, then take the uncooked meal to a local bakery. There, they could leave their crocks in the big, hot ovens as they cooled overnight. Even when switched off, the residual heat would slow-cook the ingredients, resulting in a tender, fresh-cooked stew called cholent by morning.

When Irving Nachumsohn learned about this tradition from a relative, it sparked something in his mind. Born in New Jersey in 1902, Nachumsohn’s family moved to Canada during WWI. There, Nachumsohn studied electrical engineering, later becoming the first Jewish engineer at Chicago’s Western Electric.

In his off hours, Nachumsohn liked to tinker with inventions. His passion for inventing drove him to study for (and pass!) the patent bar exam – a more labor intensive but more affordable way to patent his creations. Plenty of people dream of inventing, but Nachumsohn was good at it. Soon, his inventions began popping up in major department stores like Sears.

When he married, his wife joined the family business – by then a full-fledged Chicago factory that manufactured Nachumsohn’s products. Fern was feisty; the couple’s daughter, Lenore, recalled a favorite family story in an interview with Tablet: “She used to tell a story about sitting in the factory wearing her mink coat because it was cold in there. Someone came in and said, ‘pretty fancy for a receptionist,’ and she said, ‘I sleep with the boss.’”

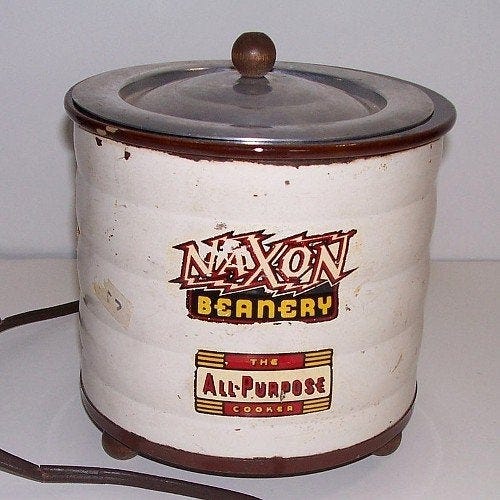

During 1945, as WWII ignited, Nachumsohn became Naxon – a safer, less German-sounding name. It’s also the name that ended up on Nachumsohn’s first slow cooker. Launched during the 1950s, the Naxon Beanery had a heating element built in to cook food slowly and evenly. Although Crock Pots eventually developed new features – spill-proof lids, removable crocks – the original Naxon design has remained constant for nearly 70 years.

Eventually, like most people, Nachumsohn – now Naxon – decided to it was time to wind down. He sold the business to Rival Manufacturing for cash (not stock, as his daughter pointed out to Tablet, though that would have made the family a fortune).

In 1971, Rival revealed a newly updated slow cooker at the National Housewares Show in Chicago. Home cooks scrambled to buy the new but essential appliance. Sales climbed from $2 million the first year to $93 million by 1975.

Today, the Smithsonian keeps one of these early Crock Pots in its collection of historically significant artifacts. The museum’s specific model came from a Pennsylvania couple named Robert and Shirley Hunter, who received their avocado-colored Crock Pot as a gift in 1974. (It’s the one pictured at the top of the newsletter!) Robert, the chef of the house, recalls using it to make halushki, a favorite of his Polish family featuring cabbage, onion, garlic, and noodles.

But if the Crock Pot had been around for so long, I wondered, why did it take off during the 1970s – two decades after it was first introduced? As it turns out, the timing was about more than Rival Manufacturing’s market reach.

The 70s were a decade of constant energy crises. As energy prices soared, energy efficiency became a core element of the Crock Pot’s branding. Not only would the Crock Pot save you time, ads promised, but it would also save you money. Even if you kept a Crock Pot going all day, it would only use the equivalent of an incandescent lightbulb’s power – far less than an electric oven. When recession-era budgets tightened, the Crock Pot could also transform cheap cuts of meat into fork-tender meals.

Inevitably, sales plateaued, then tapered. The 1980s brought microwaves, and besides, the Crock Pots already in circulation were built to last. The one thing that remained constant was the discourse around how Crock Pots impact (or fail to reshape) gender roles.

For decades, ads claimed that Crock Pots could relieve the constant pressure for working women to retain their role as homemakers. Yet today, women still spend more time cooking and cleaning than men, albeit allocated to different tasks.

One funny reaction to these gender politics is that in recent years, Crock Pot manufacturers have started targeting men in an effort to drum up new sales. In 2012, a slow cooker manufacturer called Jarden partnered with the NFL to produce a series of Crock Pots branded with official team logos. Once an homage to Jewish ingenuity, then the supposed savior of working women, Crock Pots are once again rebranded as a game day essential.

The only thing that seems certain, especially as social media cooking videos boom, is that Crock Pots are here to stay.

Something else

This week, the Delacorte Review published the culmination of three years of Abigail Covington’s reporting. The story delves into a fraught subject for Southerners – the legacy of slave-owning, idealized, Confederate general Robert E. Lee on a Lexington, Virginia, campus named for him.

Covington’s story is both a deeply researched history and an insightful profile of an African American professor who has spend decades making way for change. Here’s a snippet:

Many northerners and unionists protested the Lost Cause’s glorification of the Confederacy and soft-pedaling of slavery, but southern sentimentalists overwhelmed them, and the Lost Cause narrative prevailed as the primary lens through which people from the south thought about and remembered the Civil War era. As time ticked forward, the Lost Cause’s influence spread. The fear that Yankees might torch the southern way of life during the Reconstruction era fueled the movement and by the mid-20th century what had started off as rose-tinted recollections with Lee at the center ended up as text in school books with the general cast as a hero. One such book was Charles Flood’s Lee: The Last Years. And despite it being discredited by serious historians as nothing more than Lost Cause propaganda, it was given to incoming W&L freshmen up until the very recent past.

This is what Ted DeLaney was up against: one hundred fifty years of purposefully misleading history stuffed inside the minds of his students and their parents and their parents’ parents. To detach them from all that they knew would be an enormous task — one that DeLaney had spent years both engaging with and retreating from, careful to never ask too much of anyone at a given point. If Lee’s relationship to Washington & Lee was about leadership, DeLaney’s was about deference. Fortune didn’t favor the bold at W&L, especially if you were an outsider. And simply by the color of his skin–despite being born and raised in Lexington and having spent his adult life on the W&L campus–DeLaney remained an outsider.

You can (should!) read the full article here.

One more thing