In 2005, UC Berkeley hosted its ninth annual Art, Technology, and Culture Colloquium. One talk in particular drew people in droves–not just students and faculty, but Bay Area luminaries ranging from Louis Rossetto and Jane Metcalf (founders of Wired) to Tiffany Shlain (founder of the Webby awards).

When the speaker finally shuffled onstage, conversations quieted and everyone waited, curious to hear what he had to say. The talk was about Microsoft PowerPoint–the ubiquitous presentation software–and sure enough, he queued up a slideshow that would guide the talk.

It was David Byrne, formerly of the Talking Heads, there to talk about his PowerPoint-based book and DVD.

Before we get into all of that, it’s worth retracing PowerPoint’s history. As a child of the 90s, I can’t remember a time before PowerPoint. In fact, the first iteration of the software was created in 1984 when a computer scientist named Robert Gaskins collaborated with two developers, Thomas Rudkin and Dennis Austin, at a Silicon Valley startup called Forethought. The trio named their creation “Presenter,” hoping it would soon replace cumbersome blackboards and transparency projectors.

Presenter wasn’t initially compatible with Windows, so Gaskins turned his attention to Apple. As he recalled in a piece on BBC, the next three years brought steadily climbing sales, suspenseful negotiations and an injection of venture capital from Apple. Gaskins was eventually contacted by Microsoft, and after a few rounds of negotiations that tripled the price, sold PowerPoint for $14 million.

Gaskins retained control over the software and began running Microsoft’s first non-Seattle-based department. “This vacuum allowed my team to carry on with surprising independence for more than five years,” Gaskins recalled. “We were kept hard at work by the incentive of completing our own product vision.”

With Microsoft’s backing, PowerPoint quickly became ubiquitous. Sales soared over $100 million by 1993, accelerated by its inclusion in the Microsoft Office software bundle. By 2003, annual sales surpassed $1 billion.

Despite its popularity, PowerPoint’s history isn’t scandal-free. In 2010, NYT published an article about the U.S. military’s use of the software. “PowerPoint makes us stupid,” said Gen. James Mattis, delivering a quote that would pop up in business blogs for years after.

The public was surprised to learn that members of the military spent an enormous amount of time creating, viewing and updating various PowerPoint presentations that guided daily briefings and communication. Mattis’ comment, though taken out of its full context, is still apt; his objection was that anything that attempts to make the complexity of conflict neat and easily manageable is inherently incomplete.

It’s a lesson NASA was also forced to learn, after the 2003 Columbia shuttle explosion. The space agency also used PowerPoint, which quickly became confusing when loaded with scientific and engineering plans. Edward Tufte, a Yale professor and key critic of PowerPoint, blamed the software’s ability to bury salient information in an onslaught of homogenous design elements.

War and disasters aside, PowerPoint’s ubiquity and peculiar constraints are exactly what allows people to warp and refract it in interesting, ironic ways.

This sentiment is at the heart of David Byrne’s use of PowerPoint. One slide developed when he began experimenting with PowerPoint’s built-in library of shapes:

"I began this project making fun of the iconography of PowerPoint, which wasn't hard to do, but soon realized that the pieces were taking on lives of their own,” Byrne recalls. “This whirlwind of arrows, pointing everywhere and nowhere–each one color-coded to represent God knows what aspects of growth, market share, or regional trends–ends up capturing the excitement and pleasant confusion of the marketplace, the everyday street, personal relationships, and the simultaneity of multitasking. Does it really do all that? If you imagine you are inside there it does."

Byrne isn’t the first or the last person to bend PowerPoint into its own peculiar artform. In December 2018, author Dana Schwartz published a PowerPoint presentation on Twitter in which she made a forceful argument for why Belle should have chosen Gaston (in the 1991 Disney classic Beauty and the Beast). The fact that corporate salespeople set out each day with crisp suits and persuasive slide decks is exactly what gave Schwatz’s argument its off-kilter, bizarre vibe–what made it so funny.

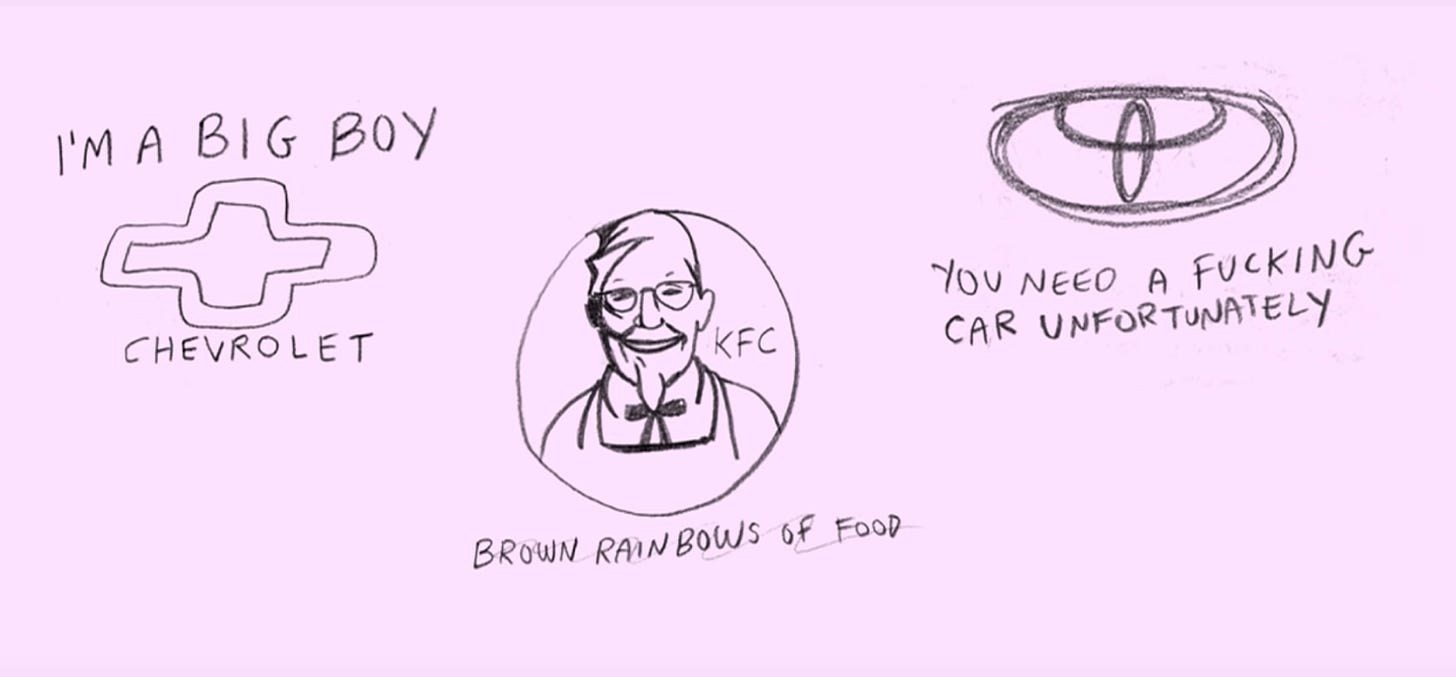

It’s also what gave my favorite PowerPoint, Lisa Hanawalt’s 2015 XOXO presentation, extra zing when she unveiled her suggestions for corporate slogans:

All of this begs the question: Is PowerPoint to blame for failures of communication, or have we been viewing it in the wrong light all along?

At that Berkeley presentation, Byrne suggested users should bear more responsibility. “[Y]ou can't blame it on PowerPoint,” he told the audience. “You see it on the TV news, everything's filled with graphics and icons–it has the illusion of content but there's very little being communicated."

Something else

The Succession soundtrack is on Spotify, which means you can listen to it while reading the Caroline Calloway essay. That is all!